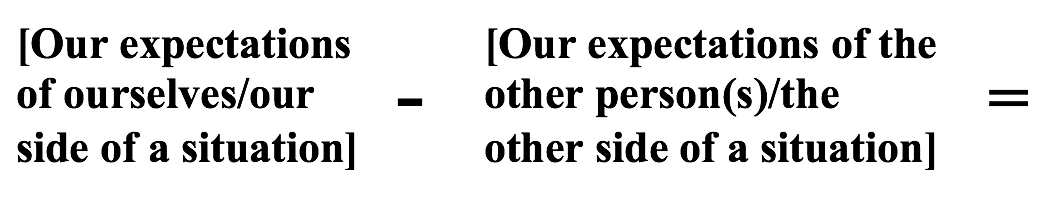

If the concept of “dispute” could be narrowed down to one equation, it might provide broad insight and simple, useful directions to professionals who deal with disputes. After years of managing people in conflict with each other and people in conflict with the legal system, I would propose the following simple equation to describe any and every dispute:

If the left side of the minus sign is greater, there is no dispute. If the right side of the minus sign is greater (creating a negative value), then there is a dispute. I argue that this basic, all-encompassing formula applies to all disputes and, thereby, points out the centrality of expectations in these situations. Based on these conclusions, I will then argue that mediators could improve and simplify their interventions by placing expectations at the focus of the mediation process.

Explanation

A dispute is an active clash between two people, whereas “conflict” is a broader concept that includes tensions and disagreements between people who are not necessarily engaging each other directly. Two people can have clashing interests, but it is only when they expect things of each other that they are in a dispute. And if Person A expects something from Person B in a situation that Person A is not involved in, then Person A is more of an intervener or third-party, rather than a disputant. If both people are involved in the situation, each will have expectations for themselves (“I can handle that” or “I shouldn’t be dealing with that”) and expectations for the other (“You shouldn’t have to do that” or “Why haven’t you done this yet?”).

The reason that there is a minus symbol between the left and right side is that if we expect more from ourselves than the other, there is no dispute—we will either do the thing ourselves or not (but also not expect the other to do it either). Then, when we expect something from someone else that we do not expect from ourselves, the other person will either meet this expectation (heading off the dispute) or will not (because they can’t/don’t expect themselves to have to comply). As a result, when people expect more from each other than they expect from themselves, they are in a dispute.

The reason that the formula is a comparison of expectations, rather than esteem or some other variable, is that without expectations there is no dispute. If there is only past action and resulting feelings, then there is no reason to continue interacting and no dispute (consider trying to mediate between two former friends who are each fully comfortable never talking to the other again). Commonly, however, past transgressions often come with future expectations, such as an apology, reimbursement for losses, or an assurance that similar transgressions will not occur again. Thus, unfulfilled expectations of each other are the reason that the parties continue to fight with each other despite the unpleasantness of the conflict.

This formula explains why certain people habitually find themselves in disputes–they expect little from themselves and much from others/the world (in the ADR Bible**, entitlement is the most grievous sin). It also explains why some people have managed to glide through life free from disputes—they expect much from themselves and little from anyone else (in the ADR Bible, selflessness and empathy are the ultimate virtues).

**Note: I’m not referring to an actual book here. There is no ADR Bible; unless you count the actual Bible.

Application

So, what tips or procedures can be gleaned from this schema? I suggest that dispute resolution professionals (1) ask the parties early in the process about their expectations of the other side, (2) help them to identify and reflect on the values that underlie those expectations, and then (3) focus on each of their expectations for themselves in the situation. The details and inner-workings of this approach would play out as follows:

- “What are Each of You Expecting from the Other?”

After the disputants have vented their stories, the ADR professional should ask each disputant about his or her expectations of the other. This action would force them to be concrete in defining the dispute, offering details rather than expressions of general dissatisfaction. Defining the dispute shifts the parties from complaining about each other to formulating demands that can be compared, considered, and explored for potential overlap. Disputants seem to find it easier to complain than to ask for something, and shifting from reciprocal complaints to reciprocal demands is a shift from a bickering match to a negotiation. This change in mindset is discernible and can be jarring—consider how many laundry lists of complaints are cut short with an exasperated, “What do you want from me?” (i.e., “What are you expecting from me?”). Also, a focus on the expectations of the other side may focus the parties on the future, elevating the discussion from past misdeeds to available solutions. Finally, focusing on expectations of the other side will bring forward the larger, critical expectations that delineate the dispute (remember, the right side of the equation is larger in the mind of each disputant).

- “What is Important to You about Your Expectations from the Other?”

Next, the dispute resolution professional can help the parties analyze the values behind each of their expectations of the other. While motivations are not always stated upfront, each disputant will have deeper personal values that underlie the expectations they have for the other side. If their expectations are worth engaging in unhealthy conflict, they will be profoundly important to the disputants. Describing and deliberating on these values fulfill a number of productive functions in handling the dispute:

First, this conversation allows the parties to express the emotional core of their positions—the values on which they hinge their demands of the other side often have a strong emotional component. This expression of the emotional core then shifts the emotional component of the discussion to a more rational level. When the emotional centers of the brain—the fight-or-flight mechanisms of the lower brain structures—are active, they short-circuit the more rational levels, hindering problem-solving and decision-making. So, negotiating with emotions is akin to offering an amount of money to someone to not be afraid; whereas, speaking to someone about their fears is akin to psychotherapy, allowing them to think through and rationalize the thought processes behind their fears.

Furthermore, when the parties express the emotional core behind their expectations, it brings each party to express the motivations behind their demands. While unassisted disputants tend to focus on stating complaints and demands instead of explaining them, this conversation reveals their internal thinking. This may lead to overlaps in values and goals between the parties (e.g., “It appears that both of you believe in the value of a close parent-child relationship”), from which the dispute resolution professional can build a mutual agenda for negotiation. However, even when they do not overlap, discussing underlying values may better allow the parties to understand each other and discuss their differences. Because these values are internal to each disputant, they cannot be debated or contradicted—for better or worse, it is what the other side is thinking. If they argue over their respective interpretations, they will be using their differing perspectives to offer each other new ways of thinking, they will be debating perspectives rather than attacking each other personally, and they should be better able to “agree to disagree” on what they cannot change and negotiate with their differing perspectives in mind.

Finally, stating the values behind their expectations of the other side will establish a high benchmark (the right side of the equation being larger than the left side) from which each disputant’s expectations for themselves can be measured…

- “…And What are Your Expectations from Yourself in this Situation?”

Disputants are often only able to discuss their own contributions to a conflict after they have fully expressed their demands (their expectations from the other side) and the emotions and justifications behind these demands (the values underlying these expectations). So, after a lengthy discussion of expectations and values, shifting the disputants from a focus on the other to a focus on themselves should feel logical and organic. And, because the parties have expressed high expectations of each other and then argued that these demands are supported by their personal values, they will then be confronted with applying these standards to themselves. Human beings have a deep psychological tendency toward consistency and should find it mentally grating to demand one standard from the other side and then apply a different standard to themselves.

I would predict that, placed in this situation, most parties will make a reciprocal demand/offer (i.e., “I’d be willing to do action in line with this value system if the other side did as well”).

Thus, I would argue that the above formula is a useful schematic for defining disputes and that the proposed three questions will best solve the equation and resolve the dispute.